When I started this newsletter, I promised content on something I’ve been calling naturalistic theology. I’ve used this term to refer to my attempt to synthesize what’s best about spiritual and non-spiritual worldviews, without shafting or catering to either side.

This week’s letter is an entry on that topic.

Enjoy!

A naturalistic account of natural law

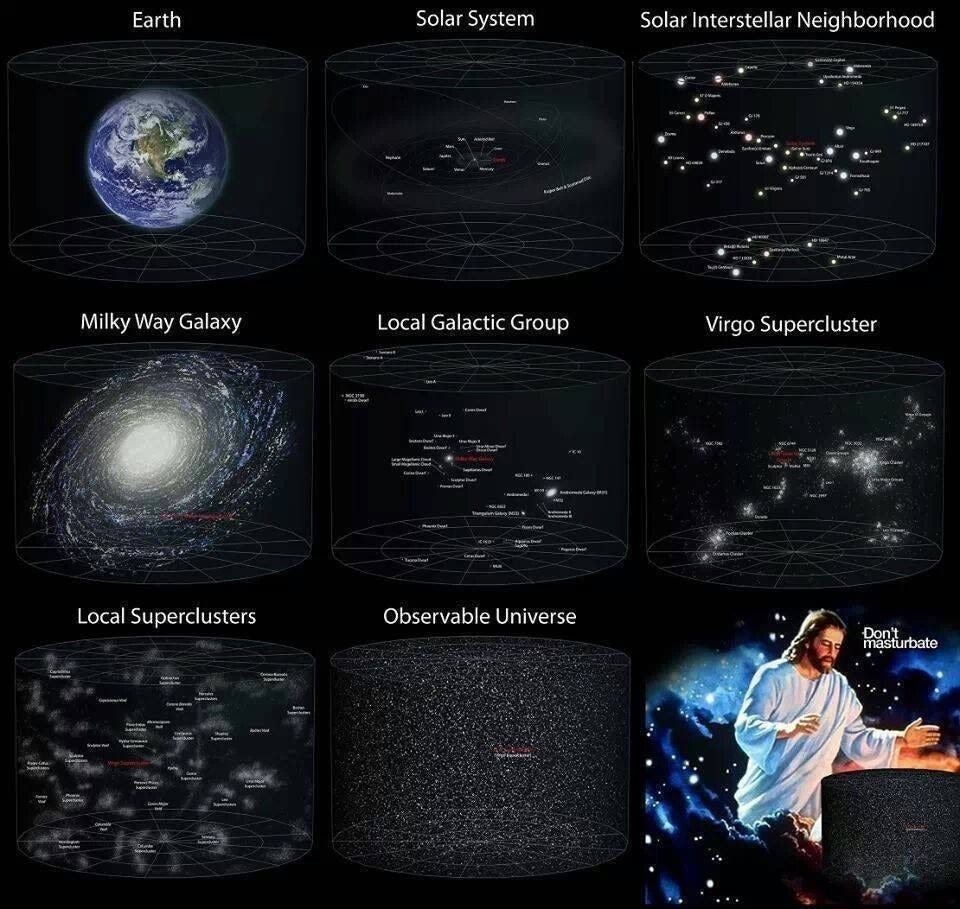

I thought this was pretty funny:

Though amusing, the humor feels a teeny bit dated to me. It reminds me of when I was high school, when (if memory serves) talking heads raged over whether Creationism could be taught in schools. Those old battles feel a bit quaint in our era of riot and pandemic, don’t they?

Where did that particular version of atheism go? The atheism of Richard Dawkins and Neil DeGrasse Tyson? The (angrier) atheism of Cristopher Hitchens? It’s not exactly ascendant at the moment, though it’s not gone either. Perhaps it won a quiet victory in the minds of nerdy mid-2000s highschoolers, many of whom ended up in STEM or software engineering careers, and who still take atheism for granted as adults.

Perhaps this leadup makes it seem like I’m getting ready to checkmate the atheists. But I’m not. There are many forms of atheism, some of which are quite respectable. In any case, the ‘Reddit atheism’ of our image above is not particularly dangerous, so I don’t exactly think it needs a takedown.

In any case, it’s time to overanalyze this meme. Perhaps I can thereby offer something useful on the topic of the natural law.

Specificity in mockery

Mocking jokes assert something specific about the object of mockery. For example, maybe our meme alleges that “Christians would have you believe that a man in the sky cares what you do with your genitals” - which is silly, it suggests, because there is no such man in the sky. The upshot is a less propositional, more affective “haha, look at the dumb Christians.”

Is this the precise essence of the joke? I don’t think so. The ‘man in the sky’ bit is too surface level, too literal, and also not that interesting. I think our meme has something sharper to say.

Perhaps its assertion is: “Christians would have you believe, contrary to all evidence, that the uncaring physical universe makes human-scale prescriptions for your behavior. But this is obviously not true, as there are no such laws on that scale, and therefore no rules regarding whether you should touch your genitals.” Therefore, “haha look at the dumb Christians,” etcetera.

This seems closer to the point.

So what do we think? Does the uncaring physical universe make human-scale behavioral prescriptions? Are there natural laws of any type, and if so, what is their scope?

Physiological self-interest

Let’s say that our atheist Redditor, at least initially, is fully against the idea that the universe ‘prescribes’ anything at all.

I think this view can be quickly dispensed with.

I’ve heard it said that “fortune favors the bold, but fortune also favors those who don’t drink bleach.” As far as behavioral prescriptions go, ‘don’t drink bleach’ is pretty unobjectionable. It’s also human-scale: “you there, Bob - don’t drink the bleach.” And lastly it’s the sort of thing which was ‘come up with’ by the universe, not by people. If it is granted that sickness and death are undesirable, and that drinking bleach leads to those, it seems written into the cosmos that the human animal ought not do that thing - as long as this ‘ought’ is understood in a quotidian, non-dogmatic, non-categorical sense.

I bet our Reddit atheist cedes the point. But they might deny that it has anything to do with their meme. Perhaps they’d say:

Yes, the universe has physical laws, and yes the laws of chemistry and biology are among them. And it’s therefore obvious that (in some normal, practical, non-dogmatic sense), you shouldn’t drink bleach, and that this prescription is (in a similarly normal and non-dogmatic sense) written into the universe. Drinking bleach has an obvious, direct, and harmful physiological result. But the category of injunctions like ‘don’t masturbate’ has nothing to do with physical well-being. So there no such prescriptions of that type.

In accepting the bleach-drinking example, our interlocutor has ceded the existence of ‘laws of the universe that make human scale prescriptions.’ But to distinguish the masturbation rule from the bleach-drinking rule, he suggests that lawful prescriptions only arise in the case of immediate and physical costs and benefits. Perhaps only biological, chemical, and physical-mechanical laws are meant to be included.

Economic laws and other direct causality

So are ‘immediate and physiological’ prescriptions the only prescriptions to be found in our uncaring universe?

I think we can go further while remaining on solid ground. We’ve all heard the fable of the Ants & the Grasshopper. The Ants work to save food all summer, and so they survive the winter, while the Grasshopper plays fiddle all summer and starves.

You might call this law and corresponding prescription economic in nature. If you don’t save food, you won’t have any. If you drink bleach, you’ll die. Nice and causal. Almost written into the universe, you might say.

What might our interlocutor think?

“Yes, like bleach-drinking, economic laws clearly apply. But it’s just different from what we’re making fun of. I’ll cede that there are many universal laws of different types, from the biological to the chemical to the economic, as well as other causal pathways without clear academic labels. I’ll also cede that many of these could be said to make specific prescriptions in different circumstances, since our wellbeing depends on adhering to those laws. But this moralizing about masturbation and many other topics is *invented* by people. It is not objective, coming from the universe. That’s why it doesn’t work.

We might say that our interlocutor will cede the existence of non-dogmatic ‘prescriptions’ in in all cases where behaviors have direct and important causal consequences. But he contrasts these with ‘created’ prescriptions, the kinds that come from people, and calls these unreliable.

There’s clearly something worth acknowledging here. Many invented ideologies erroneously insist that ‘their law’ is ‘The Law’. Constructed social systems often pretend to cosmic and metaphysical authority. ‘Law’ in the social and invented sense is quite different from ‘the law of the universe’.

All of that said, I’m not yet ready to cede that the moralistic anti-masturbation meme comes from people, rather than the ‘universe’. This might seem odd, but I’ll explain as best I can.

I don’t know much about how Christianity justifies its discouragement of masturbation. But spiritual systems often go in two directions in such circumstances: First, they’ll argue for a rule by arguing from the conditions of spiritual wellbeing. Second, they’ll argue for the rule by arguing from the conditions of positive social order.

Let’s explore these.

Laws of spiritual wellbeing

If in terms of spiritual wellbeing, the argument against masturbation might be that it causes one to take refuge in fantasy, encourages a mindset of addiction, and that addiction allows us to ignore our lives and the true conditions of our flourishing. Perhaps attachment to the ‘ungrounded’ rewards of physical pleasure can be a roadblock to purpose, stability, and orientation.

Whether or not you buy this specific argument, it suggests an interesting argument type. This argument type says that there are laws regarding (the thing I’m calling) spiritual wellbeing and its achievement, and that various actions are therefore prescribed or not prescribed on this basis.

If our atheist cedes that there is such a thing as spiritual wellbeing, and that its operation is lawlike, then he also might cede that the universe, in some sense, prescribes that we act or not act in certain ways, at least if we want spiritual wellbeing. And I’m confident that we do, in fact, tend to have this desire.

Laws of social order

Moralistic prescriptions are also sometimes justified by reference to the conditions of a good social order. But what is a ‘good’ social order?

As a loose referent, I’d say that a good social order is a social and political state of affairs which encourages things like wellbeing, prosperity, happiness, and proactive contribution. A bad social order is a social and political circumstance which wrecks havoc on its members, gets them killed, discourages prosperity, or engenders misery and selfishness.

If the anti-masturbation rule were argued for in these terms, it might claim that masturbation decreases desire for one’s partner, discourages procreation, supports the dependence on fantasy instead of reality (which has other negative downstream effects), or something like that. It would then tie these to a model of social function, maybe one which depends on childbearing, monogamy, or similar things.

These topics can be controversial, but thankfully we don’t have to talk about them. Because whether or not these specific things are true, but they suggest a type of argument. The argument type says that X is not recommended because X disrupts or prevents a good social order by means Y.

Are there facts, principles, or even laws about the conditions a good social order? I certainly think so. Maybe these laws aren’t known, easy to discover, or even possible to discover. But Confucius and Aristotle are worth checking out, on the topic.

Are these laws relevant to individual action? It does seem like individuals can do things to disrupt the social order, e.g. by harming and killing each other, burning things down, etcetera. Perhaps it’s possible to do good and creative things as well. I think most people will choose a positive route if they think they have the opportunity.

Is the social order desirable to uphold? It might depend on how it’s working for you. That said, even revolutionaries tend to want to start something new and better, and so opponents of the social order may still support some social order. If their proposed social order is possible, the conditions of its advent (in reality) might be lawlike.

Our atheist might never agree that anyone should categorically do this or that. But maybe he will cede that there are ‘principles of the creation of a good society,’ and laws about what sorts of things support or improve it. And if he cedes this, he may be forced to agree that the universe prescribes things to those who might contribute to such an order, if those people might also stand to gain from its creation or maintenance.

Conclusion

I believe the concept discussed here is usually referred to as ‘natural law’. There may be many such natural laws, or perhaps one interconnected set - not only ruling our physical wellbeing, but also our mental stability, spiritual wellness, skill development, societal function, agriculture, music, and everything else. It’s the structure of reality itself, beheld without losing the context of our goals and desires.

Atheists are often allergic to moralizing. They’re also allergic to the idea that great and incomprehensible powers are making rules about what we should and shouldn’t do. Believe me - I spent years as an aggressively godless anarchocapitalist, and I think I know where they’re coming from.

But maybe even hardline atheists, like my own past self, might find something useful in the idea that The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom. Don’t worry, you don’t have to believe in a ‘big man in the sky’. You don’t have to anthropomorphize anything. But consider respecting, or at least acknowledging, that mass of law and order, those universal demands whose source we don’t entirely understand.

Consider respecting it, if only out of self-interest, that you might live well and achieve everything you’re looking for.

Thomas Aquinas is not bothered by your memes, for he puts his faith in Providence.

Further reading

I heartily recommend The Gods of the Copybook Headings, by Rudyard Kipling.

Oh man, I loved this so much. In particular:

But maybe even hardline atheists, like my own past self, might find something useful in the idea that The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom. Don’t worry, you don’t have to believe in a ‘big man in the sky’. You don’t have to anthropomorphize anything. But consider respecting, or at least acknowledging, that mass of law and order, those universal demands whose source we don’t entirely understand.

Really echoes this part of my worldview I've been putting into words over the past few years. I've usually said, "Look, I don't think there's God [meaning an anthropomorphized creator entity]. But I do think there's God [a coherent set of things (ways of living and being) that are good, fundamentally]."

But I really like the way you've stuck with making a claim that's even weaker in some sense and yet also much more thorough: "There is God [a coherent set of laws/principles that govern the universe--including those that govern the creation, functioning, and maintenance of a society that supports the flourishing of its members, and the behaviors/general way of living that contribute to such a society]."

Thanks for writing and sharing!

ps, let me know if my paraphrase misses anything

I enjoyed this post, comparing God with the rules of the universe is an intriguing concept! But isn't it sort of attacking a strawman? Does anybody completely deny ethics or virtue (half-genuine question, I know plenty of atheists but no hardcore anarcho-capitalists)?

I think a hardline atheist is very likely to agree that no Big Man in the Sky is telling them not to inject heroin, but that it would be a bad idea regardless to inject heroin. In general I'm not sure anybody disagrees with

> Because whether or not these specific things are true, but they suggest a type of argument. The argument type says that X is not recommended because X disrupts or prevents a good social order by means Y.

But where they might disagree is the epistemic standard required to show that X causes Y. I think rejecting religious tradition or dogma as proof for this type of statement is a defensible idea, even if you think some of these laws are difficult or impossible to comprehend rationally. (Because why would religion be a better way to comprehend them?)

Or are you indeed making the stronger claim that religious traditions, even though they might tend to anthropomorphize God a little too much, still have information / wisdom about it?