33.

Today, I’d like to discuss love. I’ll be discussing love in all its forms, from the platonic to the romantic and so on—and I’ll argue that in other people, we find a divine mystery. That is to say: a mystery apprehended in the manner of a mystery cult.

What is a mystery cult? I don’t mean to refer to cults whose practices are kept mysterious to non-initiates, but rather religious cults which practice the contemplation of divine mysteries.

What is a divine mystery? By means of an example, many tribal cults contemplate fertility —the fertility of the earth, of women, and so on—in an effort to come closer to the secrets of the cosmos. Comparably, Catholics contemplate the Mysteries of the Rosary, moments wherein divine truth was revealed in the life of Jesus.

So far so good?

Let’s get into it.

Friendship is a mystery cult

In our brief human lives, we seek good things.

But we also err. We seek what we think is good, but which isn’t: a bad relationship, a harmful substance, a bad career path, and so on.

If we want good things, truly good things, we have to know what goodness looks like.

So, we set about figuring that out—through rationality, through trusting our gut, through conferring with others, and so on.

We may be tempted to ask: are there many independently good things, which are good in incommensurable ways? Or does everything good partake in one ‘goodness’, one substance or essence that surpasses particularity?

While good things are clearly distinct in material character, I like Plato’s framing in The Symposium, wherein Diotima claims that “the only thing people love is the good” (206a), and that ‘the beautiful’, which I here take as mostly interchangeable with ‘the good’,

… exists on its own, single in substance and everlasting. All other beautiful things partake of it, but in such a way that when they come into being or die the beautiful itself does not become greater or less in any respect, or undergo any change.

— Symposium (211b)

The relationship between ‘the good’ and ‘the beautiful’ can be and has been debated. Personally, I think we sense beauty where we believe goodness is present — like a nice aroma, indicating good food—and in erring, surmise beauty in a place where goodness is absent—like a nice aroma hanging around poisoned food.

Enjoying this post? I hope you’ll support me in making media about philosophy, history, and the classics.

Or keep reading…

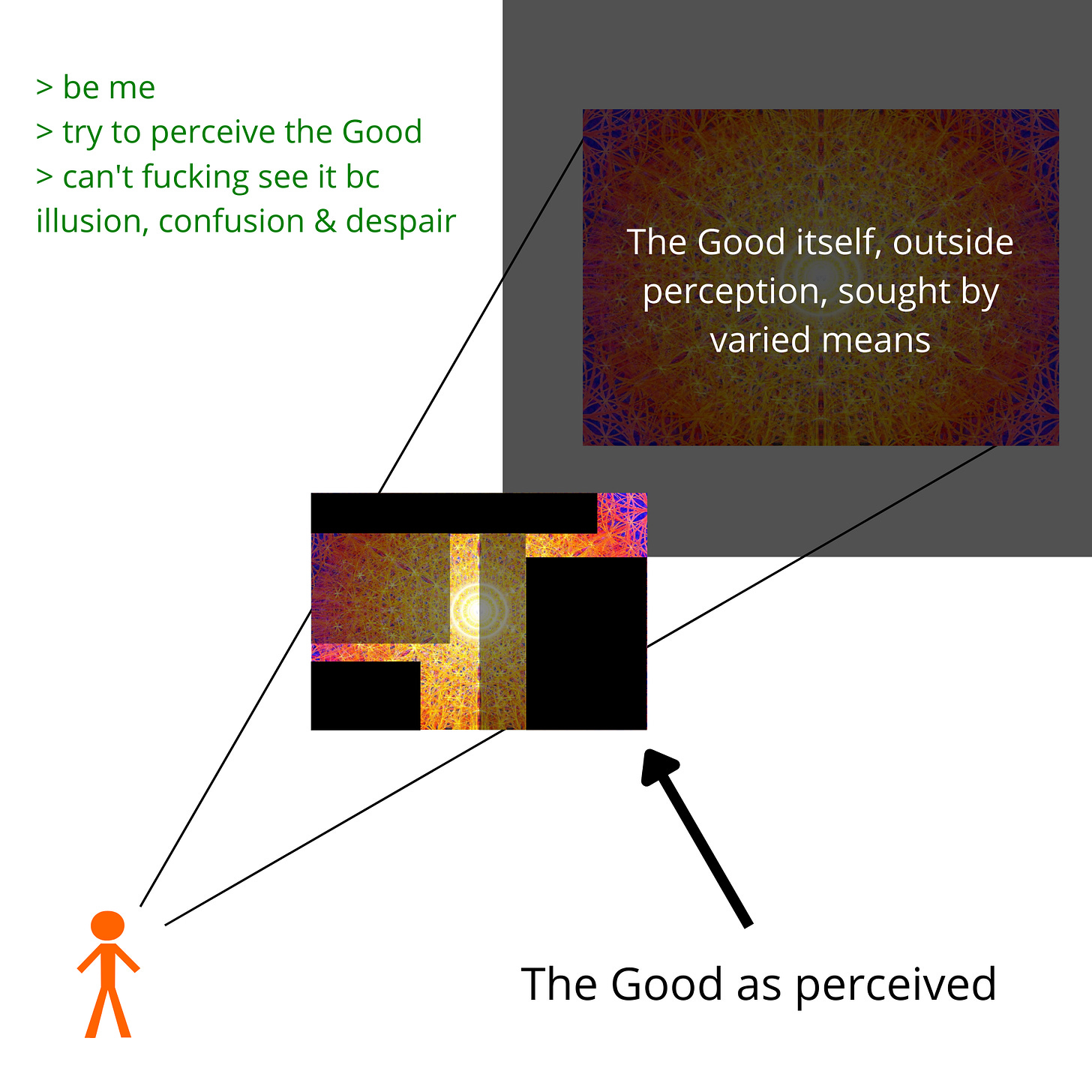

For the sake of the argument, let’s run with Plato’s frame, and say that while man seeks ‘the good’ itself, his access to it is necessarily gated by a perception which is frequently limited or incorrect.

We try our best to see the good, but we are flawed. We are confused, and our confusion is entangled with despair. So in some places, the good is apparent to us, and in other places, our perception is muddy. In further places, we are entirely blind.

So much for our perceptions of the good. What about other people?

We share perceptions with others, but we also disagree. What they love may be hateful to us; what they hate may be lovely to us. If ‘goodness’ is a real thing which shines through and is found in the world, we can note a few ways two people’s goodness-perceptions may relate:

When we’re on the same page, we vibe. We coordinate. It’s a joy to find someone who ‘gets it’—whose sense of what is valuable is importantly symmetrical to our own.

Of a close friend, Rumi is supposed to have said:

Why should I seek? I am the same as

He. His essence speaks through me.

I have been looking for myself!

Of course, much of the value in seeking others is that they are not identical to ourselves. They have a different angle.

We often find in another person that they ‘get’ something about the universe (and what matters, and how to approach it) that we don’t:

This other person’s distinctive encounter with the universe has left them with admirable qualities and virtues. They have an interesting perspective; they have an adept way of approaching the good. They specifically have an approach that we do not understand. Even if we sense it intellectually, it’s unnatural to us, because it’s not our own.

Like the members of a fertility cult, we have apprehended a mystery. We sense a clue to what is essential or desirable. And if the pull is strong enough, we go after it.

Through interaction with another person, we can witness the exercise of their virtues. If we learn from them, we may begin appreciate some new-to-us goodness in the world—or rather, another facet of the one goodness, of which all good things partake. Our understanding improves, and we are bettered by the improvement.

In this way, friendship draws us closer to what we love most. Even ordinary friendships carry the limn of what Aristotle called ‘friendships in virtue’, and what some Christians have called brother-or-sisterhoods in Christ.

As we are drawn towards others, we are draw closer to that higher source from which all love stems.

If you enjoyed this and want to support my work, I hope you’ll check out my Patreon or click subscribe:

sweet art! and a very sweet message too