11. Mastery as good taste

Extremely skilled people display a responsive awareness of subtle things.

Week 11

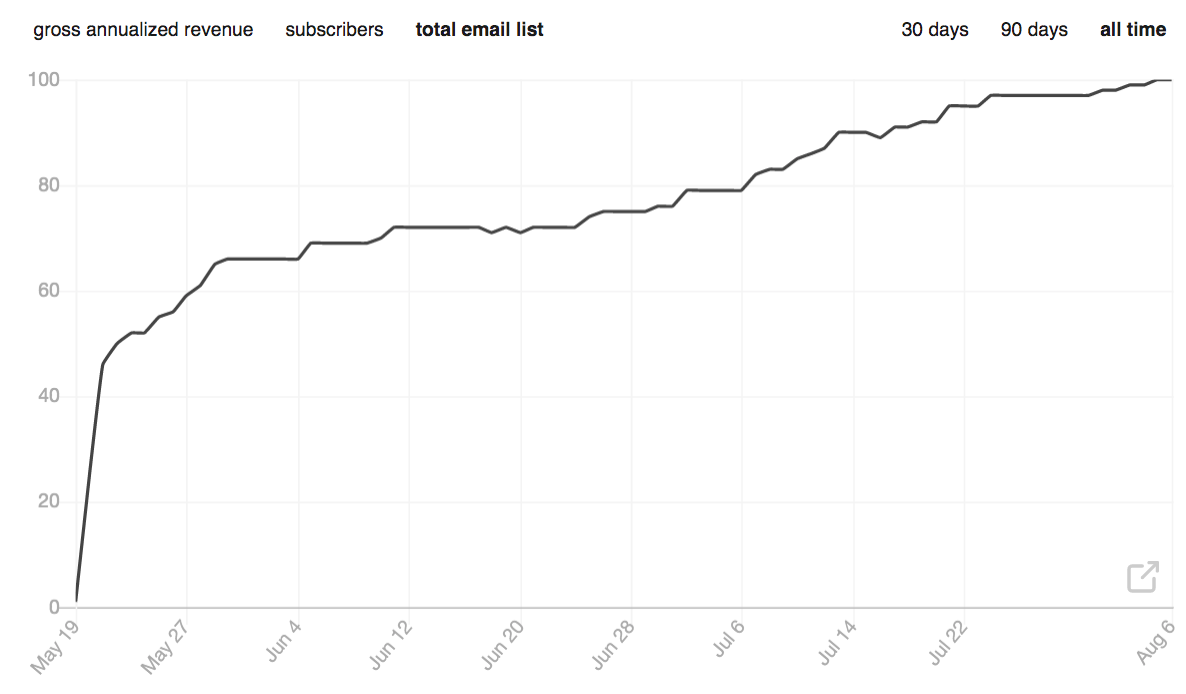

A milestone!

For me, writing is always a little brutal, but this has been the most fun & productive writing experiment I’ve attempted. Thanks for joining me!

A responsive awareness of subtle things

This week’s essay will discuss a connection between skill and taste. It’s an improved version of something I wrote back in 2018.

Let’s jump into it.

Correct action is specific

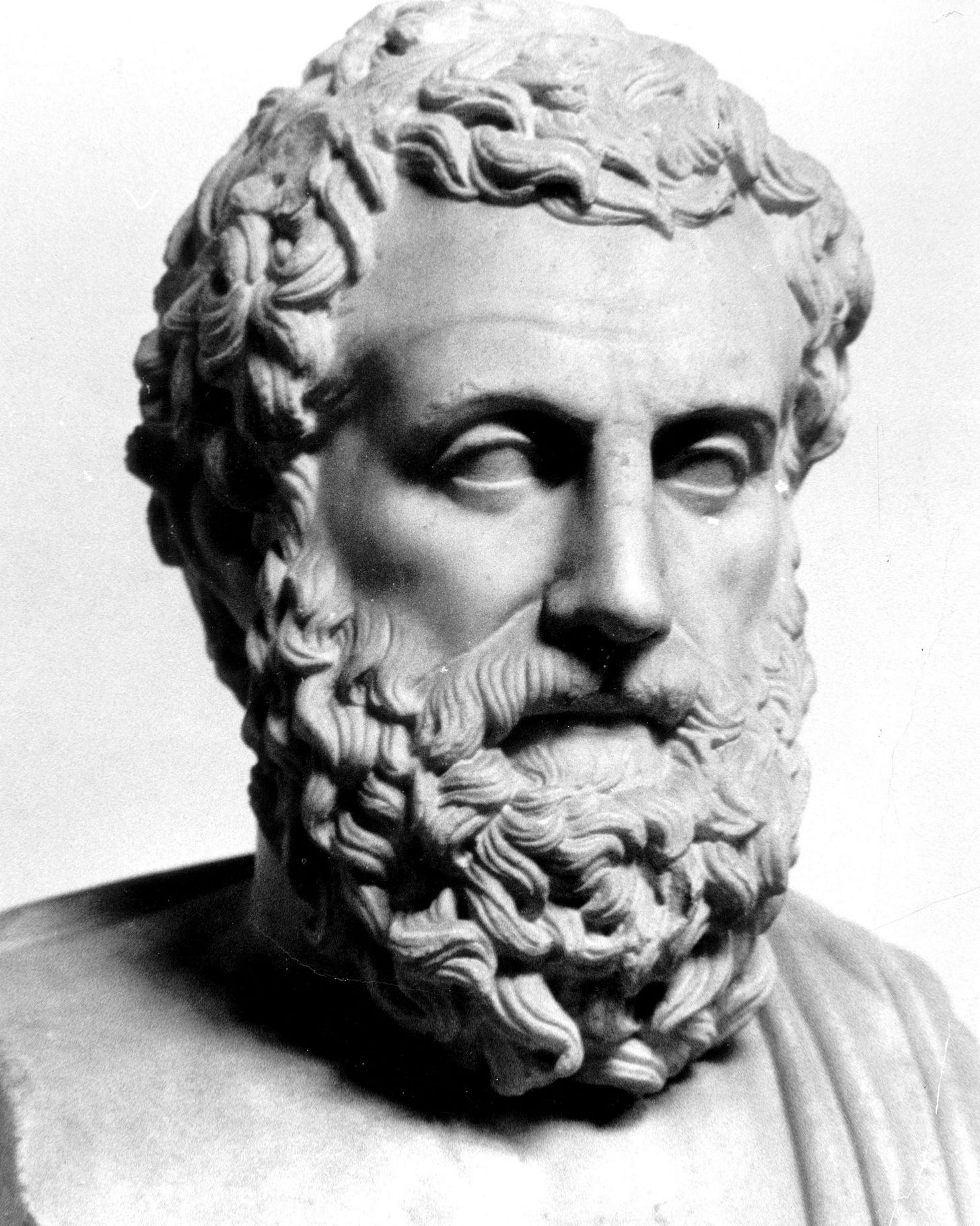

Aristotle describes virtue as a middle way. Being ‘too brave’ is rash; being ‘not brave enough’ is cowardly; we should avoid the extremes, and live somewhere in between.

But if you try this in practice, you might find yourself asking: which course of action is ‘too brave’ or ‘not brave enough’? Among the many possible paths, which is the reference point, by which excess or insufficiency are measured? Where do we place the ‘zero’?

Charging the hill seems brave. Or is it rash? (The enemy cavalry looks deadly, and our numbers are few…) Or, more strangely - could charging the hill be cowardly? (Perhaps true bravery accepts the dishonor of retreat, sacrificing pride for a greater chance at victory.)

It’s tempting to pick a course of action without looking. It’s easier to rely on heuristics and rules-of-thumb. But every situation is distinct, and broad guidelines will be less excellent than approaches that respond to a situation’s specific character. If the aim of virtue is correct action, correct action is ultimately the action that works in the situation at hand.

You don’t want to always turn left, or always turn right; but neither should you ‘always drive in the middle’.

To get where you’re going, you need to turn with the road.

Skill and correct action

If virtue aims at correct action, maybe virtue has something to do with skill. After all, what use is skill, if it doesn’t help us act well or get good things to happen?

Skill turns mundane objects into excellence. The juggler turns balls and pins into a magnificent performance; the chef turns flour and eggs and butter into a meal.

And while high quality tools (like $350 juggling balls or farm-raised duck eggs) may enhance the work of skilled and unskilled individuals alike, these are liable to be a distraction for the amateur, because tools aren’t the essence of skill; decisionmaking is. The master’s skill shines through even when his tools are wanting:

From the moment we grasp the tools of our trade, we’re offered a continuous stream of opportunities to decide what to do. The master handles these opportunities best, and nuanced and correct action flows from his fingertips, almost regardless of context and circumstance.

Within 60 seconds of engagement, the beginner makes one right decision in a domain, while the amateur makes 10 right decisions, and the master makes 100 or 1000 or more.

Skill as felt understanding

Skill is internally experienced as a felt understanding. To a juggler, a ball is not just a ball; to a master guitarist, the guitar is an entire world. Deep knowledge of something enriches our experience of it.

If we improve and sculpt this felt understanding, we improve our ability to make correct decisions in a given amount of time. We craft and refine ourselves towards the expression of an incredibly intricate ideal.

But at the beginning of the day, the clay of the mind is simple, shapeless, ugly. We must sculpt it towards a unique and patterned shape. To do this, we must know the clay accurately. We must become entirely committed to working the clay we have, not daydreaming about the clay we think we want.

We must sit for long moments with our natural, preexisting responses and reactions to the parts of reality we want to master. With attention to and engagement with those responses, we can shape them towards elegance and function.

With years of refinement, we might achieve mastery.

Essentially, what we are developing is taste. Refinement. Aesthetics. A responsive awareness of subtle things.

Developing taste

A person on track to mastery constantly asks about the objects in their domain: what do I like about this? What don’t I like about it? How do I feel when I touch and sense it? What is amusing or bizarre? What is annoying or gross? What is harrowing, and what is merely horrible? What is gently nourishing, and what is merely gentle?

How can I shape it? How does it shape me?

The person seeking mastery asks questions like these, whether their skill deals in paints, foods, laws, formulas, words, teams, scenes, biographies, philosophies, social structures, teachers, students, leaders, followers, children, allies, physical states, mental states, communications, maneuvers, plans, arguments, concepts…

The amateur spends enough time with the domain and their feelings about it to develop distinctions and responses to more and more of reality’s features. In time, these responses synthesize, principles emerge, and structure and imminent feeling become one.

It is for these reasons that I think of mastery-seekers as aspiring artists, or at least aesthetes. (They are not only this, but they are this.)

Mastery requires impeccably good taste.

(Distinguish the above from views on which the pursuit of truth is the pursuit of ‘objectivity’, or knowledge devoid of feeling or personal meaning. This is just a world-model without one’s goals running through it.)